Normalisation of psychological treatment

Despite the remarkable progress of the last decade, negative public perceptions of psychological treatments persist. It is precisely because of these negative collective beliefs that patients with functional neurological disorders may reject any influence of psychological factors, perceive a referral to a psychologist as something negative and experience feelings of rejection and not being heard.

It is important to make it clear at the diagnosis stages that not all patients can be diagnosed as having a psychological cause, but that psychological treatment can nevertheless be extremely helpful, especially in coping with associated symptoms and/or in accepting and understanding the diagnosis.

Education about the central nervous system

The human nervous system is a complex system for controlling and coordinating bodily processes. It is made up of two branches:

Central nervous system

Peripheral nervous system

The central nervous system is made up of the brain and spinal cord. It controls many internal processes such as breathing, heartbeat, body temperature, hormone and neurotransmitter secretion. Similarly, it controls our thinking, feeling and movement.

The peripheral nervous system is the part of the nervous system located outside the brain and spinal cord.

The autonomic nervous system is part of the peripheral nervous system and is divided into:

Sympathetic nervous system: also called the fight/flight/freeze system. Its function is to activate the body. For example, when we are in danger, our heart rate increases, our breathing speeds up and adrenaline starts to be released, allowing us to escape successfully.

Parasympathetic nervous system: also called the resting and digestive system. It is activated when we are at rest. It takes care of the regeneration of the body.

The main purpose of the autonomic nervous system is to maintain homeostasis in the body. Homeostasis refers to the relatively stable and balanced functioning of the whole body.

Informing patients about the sympathetic nervous system's role in activation is crucial. This system, with an evolutionary purpose, was vital for our ancestors when facing threats. It optimized their chances of survival by dilating pulmonary vessels, enhancing breathing, accelerating heart rate, and boosting muscle strength. Simultaneously, non-essential processes like digestion were halted to prioritize escape. However, the issue arises from our body's inability to differentiate between significant threats (like encountering a bear) and minor stressors (such as daily traffic jams), triggering the same response in both scenarios. With modern life becoming more stressful, the accumulation of daily stressors can lead to persistent activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

Education on the mind-body connection

The central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the whole body are extensively interconnected. Present the FND patient with some everyday examples that suggest the interconnectedness of mind and body.

Often, FND patients dismiss the psychological factors that contribute to the maintenance of the disorder and focus solely on organic causes or physical symptoms.

Tell them that separating the mind from the body is not productive. People with conditions like Parkinson's disease also undergo psychological distress, either due to the illness itself or in reaction to it. The best treatment approach is holistic, addressing both physical and psychological aspects.

Education on neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity is the brain's capacity to adapt and react to environmental stimuli over a lifetime. These changes in the brain can result in creating new neural connections or altering existing ones. Assure the patient that this presents a positive opportunity to reshape old connections contributing to FND symptoms and establish new ones to prevent symptom relapse or deterioration.

Stress education

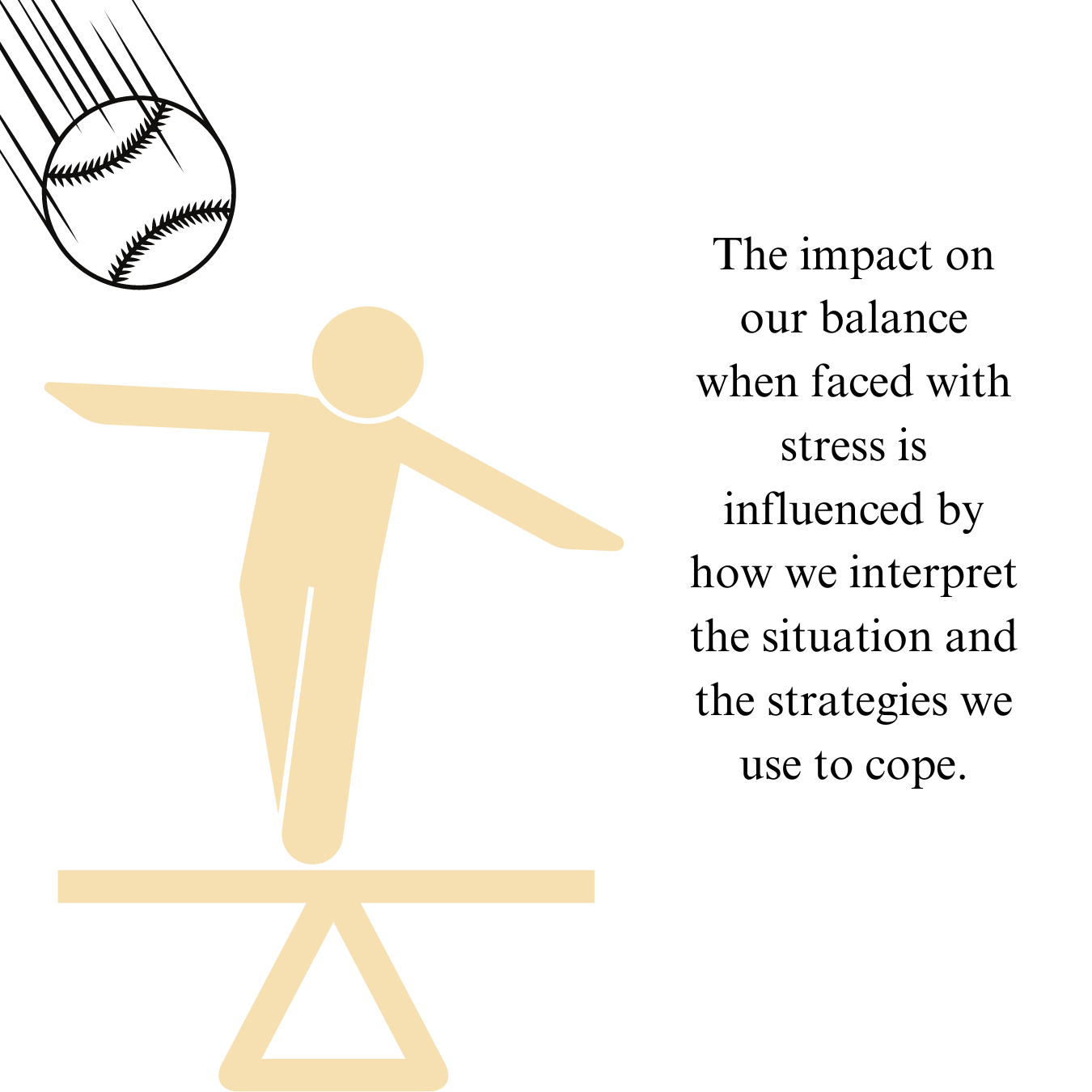

Inform the patient that stress is a reaction to a stressor, which can be an event, object, or person that disrupts our balance. Stress can manifest as a physiological, psychological, and behavioral response. It's important to note that stress can be both positive and negative in nature.

The physiological response to a stressor may be sweating, shaking hands, a faster heart rate, etc.

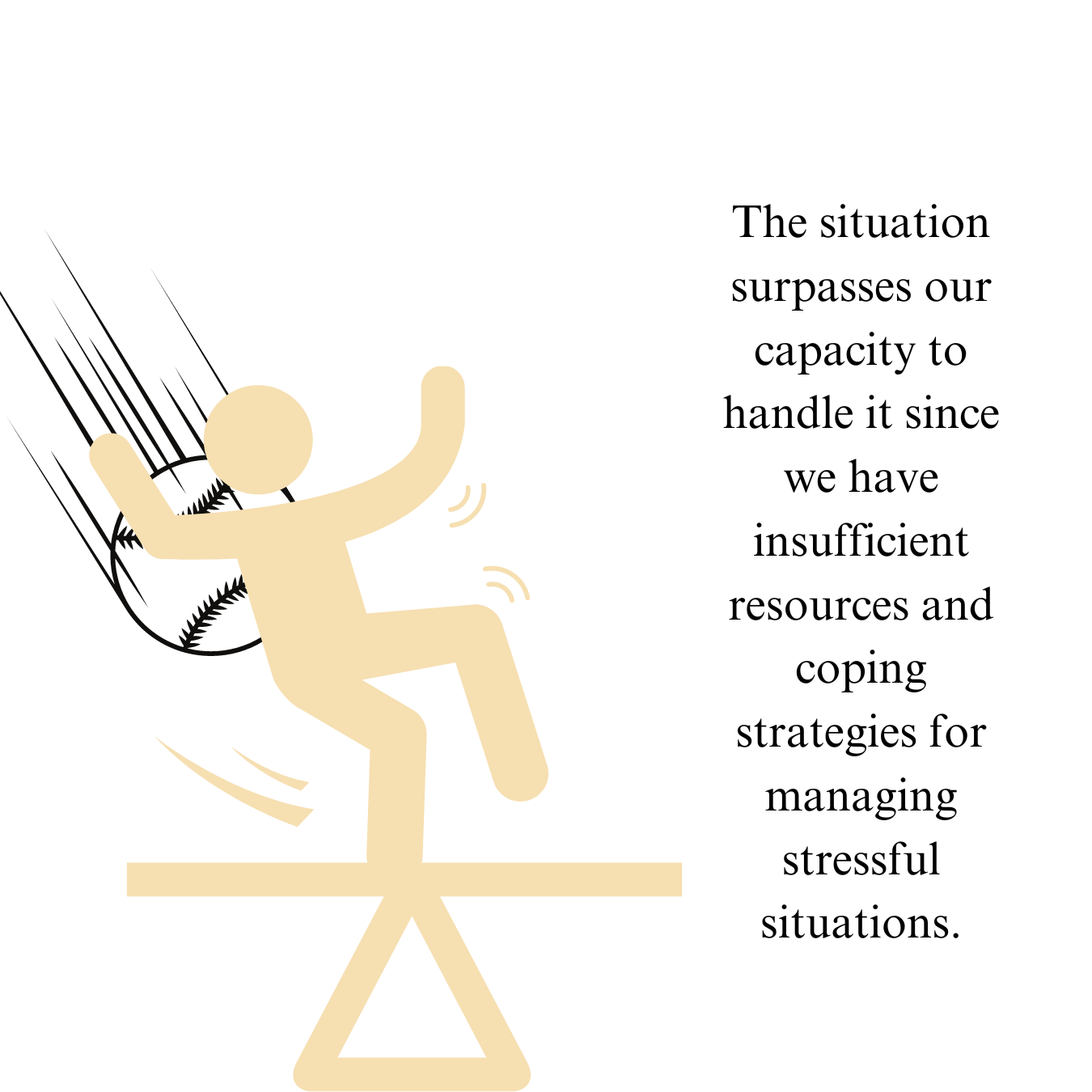

The psychological response encompasses how we internally perceive encountering a stressor. We may sense that the stressor either exceeds or aligns with our coping strategies and mechanisms. Exploring the theory of cognitive appraisal or situation interpretation (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) can provide more insight into this idea. It explains that during a stressful situation, a two-stage process occurs, leading to two different responses:

The initial step involves the individual determining if the stressor poses a risk. If it doesn't, positive stress and effective coping mechanisms ensue.

If the person perceives the stressor as a threat, a follow-up assessment of the situation is carried out. They are then asked to assess their ability to tackle the situation and if they have the necessary resources to address it. If they conclude that they have the required resources to handle the situation, they will see the stressor in a positive light. Conversely, if they feel they are lacking resources and unable to cope, they will perceive the stressor negatively.

We explain to the patient that stress management is always an attempt to reinterpret the stressful event and that psychological treatment can help to strengthen personal resources and coping strategies.

Education about emotions

Research on FND often reports that some patients have difficulty recognising and expressing emotions. Certain patients are even diagnosed with alexithymia, which refers to the inability to recognise and express emotions in oneself and others.

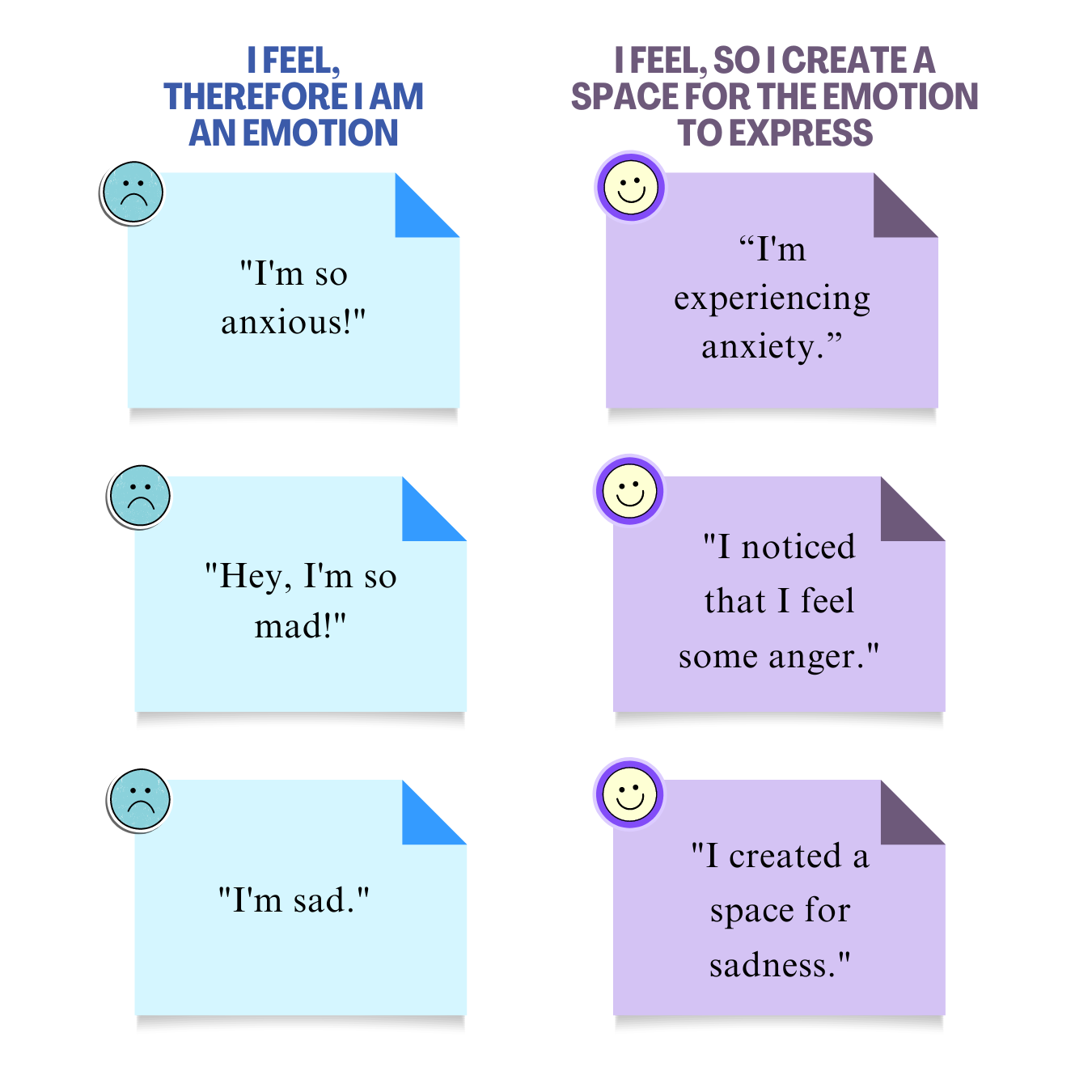

In general, you can introduce patients to different emotions, their mechanisms and strategies for managing them. Explain the difference between a feeling, as a result of electrical signals in the brain, and an emotion, as a result of our interpretation of and reaction to these electrical signals.

Explain to them that we have much more control over our emotions than we think. The key is to stop identifying with transient emotional states. This can easily be done using language:

"I am very sad today." v "I feel a little sad today."

Saying the first sentence connects us with sadness, embodying the emotion. Uttering the second sentence, we recognize the presence of the emotion within us, yet we retain the ability to release it when it is no longer beneficial.

"You made me feel..." to "I reacted to what you did..."

When we express the initial sentence, we imply that the other person is accountable for our emotions and internal state, casting ourselves as victims. However, when we articulate the second sentence, we acknowledge that our emotions stem from our own perception rather than external factors. This shift in perspective empowers us to assume responsibility for our emotional well-being, enhancing our emotional intelligence.

Education on functional neurological disorder

Explain to the patient, using metaphors or simple language, his/her subtype of functional neurological disorder and associated symptoms. Address the many names by which the disorder has been called in the past:

Conversion disorder

Hysteria

Pseudoseizures

Non-epileptic seizure disorder (NEAD)

Non-epileptic seizures (NES)

Dissociative seizures

Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder (FNSD)

Medically Unexplained Neurological Symptoms (MUNS)

Explain that FND encompasses the entire neurological system and that symptoms can be motor, sensory, cognitive, as well as patients may experience seizures. Explain the difference between patients simulating symptoms and FND and address the stigma surrounding the disorder.

The formulation of a PC model can be useful as it includes all the factors that trigger and maintain the disorder, giving the patient insight into the factors that they can start to control themselves.

Together with the patient, you can detect three types of factors:

risk factors

triggers

perpetuating factors

-

Cramer, S. C., Sur, M., Dobkin, B. H., O'Brien, C., Sanger, T. D., Trojanowski, J. Q., ... and Vinogradov, S. (2011). Harnessing neuroplasticity for clinical applications. Brain, 134(6), 1591-1609.

Lazarus, R. S. (1985). The psychology of stress and coping. Issues in mental health nursing, 7(1-4), 399-418.

van der Hulst, E. J. (2023). A Clinician's Guide to Functional Neurological Disorder: A Practical Neuropsychological Approach. Routledge.

Ziegler, M. G. (2012). Psychological stress and the autonomic nervous system. In Primer on the autonomic nervous system (pp.291-293). Academic press.