Sleep disturbances

Sleep disturbance is a common associated symptom in patients with functional neurological disorders (Graham and Kyle, 2017). Quality sleep is crucial for both physical and mental well-being. Inadequately addressing sleep disturbances can be a significant risk factor for the persistence or escalation of FND symptoms. The body regulates our sleep needs through two processes.

The process of sleep homeostasis

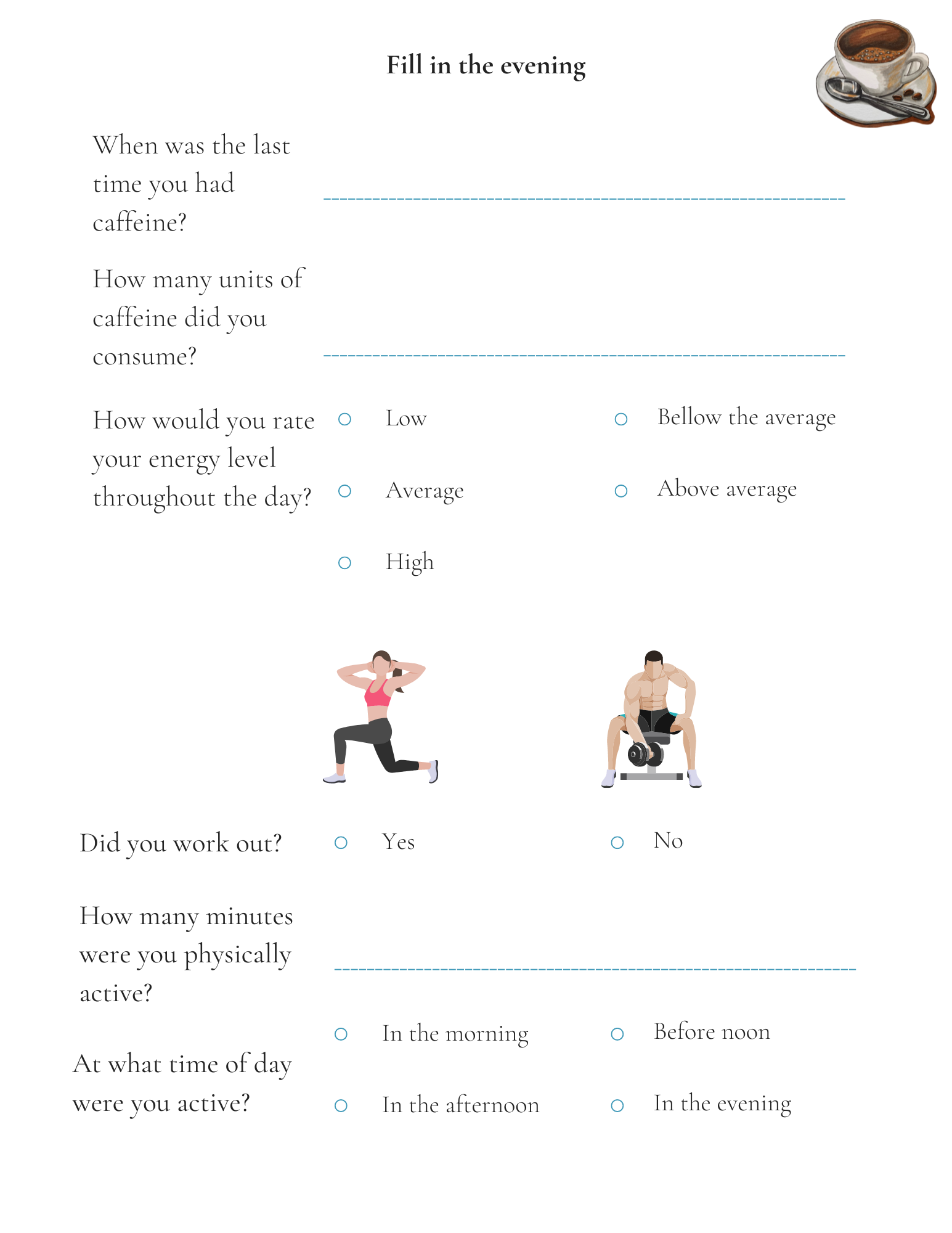

The first is the process of sleep homeostasis, which is how the body maintains a state of equilibrium. The longer we stay awake, the more the body builds up what is known as sleep pressure, which increases our need for sleep. This process is controlled by internal factors, such as the build-up of adenosine in the brain, which makes us feel sleepy, but we can also influence the process ourselves by consuming different substances, such as caffeine. Caffeine competes with adenosine and occupies its receptor sites in the brain, so we don't feel the need to sleep. But adenosine is still circulating in the blood, and when all the caffeine has been eliminated from the body, we experience a double need for sleep, as new adenosine molecules join the previous ones that were unable to bind to the receptor sites because of caffeine.

Circadian rhythms

The second process refers to cyclical changes in the body that operate independently of how much sleep we get and occur at a roughly 24-hour rhythm. Circadian rhythms are natural rhythms in the body that, depending on hormonal changes, influence when we feel sleepy and when we feel awake. One of the most important external factors affecting circadian rhythms is exposure to day and night light. Exposure to daylight in the morning triggers the secretion of cortisol, which causes feelings of alertness and readiness for activity, while exposure to night light triggers the secretion of melatonin, which prepares the body for sleep. Taking sleeping pills artificially alters circadian rhythms, which is why behavioural techniques, also mentioned below, often do not help or have the desired effect. Research also shows that a cognitive behavioural approach to treating sleep disorders (especially insomnia) is more effective than taking sleeping pills. Be sure to consult your doctor before making any changes to taking sleeping pills.

What is the role of the clinical psychologist in the management of sleep disorders?

The role of the clinical psychologist is primarily to diagnose cognitive sleep disorders and to help treat them. His role is also preventive and counselling, as he can raise awareness about the importance and hygiene of sleep, sleep management techniques and methods. He can also investigate sleep disorders from a neuropsychological perspective. His work will primarily use the CBT approach, which you can also read more about under the tab Treatment: Psychology. Below you will find some tips on how you can help yourself to improve the quality of your sleep.

A large part of CBT is exploring and actively changing the automatic negative thoughts associated with sleep. Sleep is often prevented by the negative thoughts we develop, such as:

Negative thought: 'If I don't fall asleep right away, I won't be able to function tomorrow'.

Changing your mind: 'Actually, you've already functioned on little sleep many times. You will feel tired, but it won't be the end of the world."

Negative thought: 'It's not normal that I can't sleep. It's not normal for me to be sleep-deprived, I'll get sick."

Changing your mind: ' Insomnia is common and everyone has had a sleepless night. It would take many sleepless nights to experience negative consequences."

Sleep restriction therapy

Sleep restriction therapy is a more dramatic treatment for insomnia, but sometimes the most effective. It is based on the premise of re-establishing circadian rhythms in the body and involves the following steps:

Go without sleep for 24 hours (for the vast majority of people this will be a very difficult task and they are likely to be very tired. If you can't go without sleep for 24 hours, start with step 2).

Start with your minimum sleep time (fill in a sleep diary for a week and check your minimum amount of time. If you have slept a minimum of four hours, plan to sleep a maximum of four hours the next night).

Gradually increase your sleep time (add 15 minutes of sleep each day, which means going to bed 15 minutes earlier than you did the day before).

After these steps, you can start to introduce the tips described above into your routine. In case of more severe sleep problems, consult your doctor, who will refer you to a clinical (neuro)psychologist if necessary.

-

Arendt, J., in Skene, D. J. (2005). Melatonin as a chronobiotic. Sleep medicine reviews, 9(1), 25-39.

Armitage, R. (2007). Sleep and circadian rhythms in mood disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 115, 104-115.

Clark, I., and Landolt, H. P. (2017). Coffee, caffeine, and sleep: A systematic review of epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials. Sleep medicine reviews, 31, 70-78.

Czeisler, C. A., in Gooley, J. J. (2007, January). Sleep and circadian rhythms in humans. In Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology (Vol. 72, pp. 579-597). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

Dhand, R.,in Sohal, H. (2006). Good sleep, bad sleep! The role of daytime naps in healthy adults. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine, 12(6), 379-382.

Dijk, D. J., in Archer, S. N. (2009). Light, sleep, and circadian rhythms: together again. PLoS biology, 7(6), e1000145.

Ebrahim, I. O., Shapiro, C. M., Williams, A. J., in Fenwick, P. B. (2013). Alcohol and sleep I: effects on normal sleep. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(4), 539-549.

Ficca, G., Axelsson, J., Mollicone, D. J., Muto, V., and Vitiello, M. V. (2010). Naps, cognition and performance. Sleep medicine reviews, 14(4), 249-258.

Harding, E. C., Franks, N. P., and Wisden, W. (2019). The temperature dependence of sleep. Frontiers in neuroscience, 13, 336.

Laposky, A. D., Bass, J., Kohsaka, A., in Turek, F. W. (2008). Sleep and circadian rhythms: key components in the regulation of energy metabolism. FEBS letters, 582(1), 142-151.

Mander, B. A., Winer, J. R., and Walker, M. P. (2017). Sleep and human aging. Neuron, 94(1), 19-36.

Pavlova, M., in Latreille, V. (2018). Sleep Disorders. The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.09.021

Roehrs, T., in Roth, T. (2008). Caffeine: sleep and daytime sleepiness. Sleep medicine reviews, 12(2), 153-162.

Roehrs, T., in Roth, T. (2001). Sleep, sleepiness, and alcohol use. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(2), 101.

Shilo, L., Sabbah, H., Hadari, R., Kovatz, S., Weinberg, U., Dolev, S., ... in Shenkman, L. (2002). The effects of coffee consumption on sleep and melatonin secretion. Sleep medicine, 3(3), 271-273.