Pain

Pain is a complex, highly individualised and subjective experience, involving both sensory and emotional components. The complexity of pain suggests that treatment requires an integrated, holistic approach that takes into account the multifaceted nature of pain (e.g. differentiation between different types of pain, cognitive and emotional interpretation of pain, learning through conditioning, memory, protective factors as well as risk factors).

The basics about pain

All pain starts with a stimulus. In the body, we have nociceptors that detect stimuli from the internal and/or external environment and then send information about these stimuli to the spinal cord and the brain. It is only in the brain that the sensation and perception of pain is created.

When we feel pain in a particular area of the body, it is actually a process of nociception - pain only occurs when the cognitive and emotional level, we interpret the perceived stimulus as pain.

Pain is generally defined as:

Location

Pain can be:

Somatic pain (e.g. fracture, burns)

Neuropathic painwhich occurs when there is damage to a peripheral nerve or the central nervous system (e.g. tingling, sharp stabbing, burning)

Visceral pain that is difficult to localise and attribute to a single body region (e.g. individuals who have suffered a heart attack often report previous pain in the left arm)

Psychological pain referring to the experience of negative emotions and/or emotional states (e.g. anxiety), stress and may be associated with past memories

Duration and frequency

Acute pain refers to pain lasting less than 30 days

Chronic pain refers to pain lasting more than six months

Recurrent acute pain refers to recurrent pain that lasts for a long time but occurs in isolated episodes of pain

The difference between acute and chronic pain is that acute pain has has a protective purpose to enable survival. Acute pain alerts us to danger, to the presence of pathology in the body and to the reduced usefulness of injured or diseased parts of the body. When it is no longer felt, it signals the departure of the pathology from the body and a state of restored homeostasis in the body. Chronic pain, on the other hand, severely limits and impairs the quality of an individual's healing. If it is not treated properly or only on the basis of the acute pain model, it can become more intense and consequently more difficult to manage.

Frequency refers to the frequency with which the pain is experienced - is the pain ever-present or does it occur in isolated episodes?

The root cause

The type of pain (somatic, visceral, neuropathic, psychological) can give insight into its mechanisms and underlying causes.

Intensity

The individual can describe the intensity of pain on the basis of several rating scales (e.g., 0-10, continuum mild-medium-severe...). The experience of pain is highly subjective and individualised (e.g., two different individuals may have different perceptions of the intensity of pain due to the same injury). The intensity of pain can also be assessed by asking which activities it prevents the patient from performing (e.g., eating, sleeping, moving; Pain, 2002).

Psychological aspects of pain

Psychological factors play an important role:

in the initial phase of experiencing pain (e.g. how we interpret the stimulus; associate it with a particular memory; beliefs about our own pain threshold, etc.),

perceived severity of pain (e.g. a catastrophic interpretation of a stimulus accompanied by anxiety),

worsening pain (psychological factors that worsen pain; e.g. sleep deprivation)

pain maintenance (psychological factors contributing to pain maintenance; e.g. learning through conditioning).

It could be said that psychological factors are present in any type of pain, as it is the brain or mind that interprets the stimulus as pain (Pain, 2002).

Some psychological factors that influence the pain threshold:

Anxiety and depression (Arntz and De Jong, 1994; de Heer et al., 2014)

Stress (Hannibal and Bishop, 2014; Vachon-Presseau, 2018)

Lack of sleep (Finan et al., 2013; Kundermann et al., 2004,Whibley et al., 2019)

Emotions (Villemure and Bushnell, 2002; Wiech and Tracey, 2009)

Motivation (Navratilova and Porreca, 2014; Porreca and Navratilova, 2017)

Memory (McCarberg and Peppin, 2019)

Pain treatment

Pain treatment is not standardised and requires a holistic, multidisciplinary and individualised approach. There are several ways to treat, control and manage pain:

Medication treatment

Minimally invasive procedures

Psychological therapies (e.g. CBT)

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy

Acupuncture and nutraceuticals (=substance that has positive effects and/or cures diseases)

Self-empowerment ( pain education and exploration of one's own causes and mechanisms of pain perception)

Techniques for coping with pain

-

Rubbing the painful area activates touch receptors, which reduces the sensation of pain (Monroe, 2009). It is a way of relieving acute pain.

-

Experiencing positive emotions reduces the level and sensitivity to pain (Finan and Garland, 2015; Navratilova et al., 2016; Sturgeon and Zautra, 2013).

Younger et al., (2010) have shown that looking at a picture of a romantic partner has analgesic effects on experimentally induced pain by activating the reward system in the brain.

-

Sauna bathing is thought to have positive analgesic effects due to:

Increases in BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) secretion

BDNF stimulates the growth of new neurons and relieves anxiety and depression It is active in the hippocampus, cortex, cerebellum and basal forebrain - areas involved in learning, long-term memory and executive functions.

Regular sauna use is thought to reduce the body's inflammatory response

It affects the opiod system.

Studies have found that sauna use significantly increases the secretion of beta-endorphins (Kukkonen-Harjula and Kauppinen, 1988; Vescovi et al., 1992).

Activates dynorphin. Dinorphine is an opioid that causes a deep sense of dissatisfaction and/or discomfort. As during intense exercise, high levels of dynorphin are released during sauna, which causes general feelings of discomfort when exposed to heat. However, the struggle with heat exposure ultimately activates pathways (the endorphin system) that lead to an increase in baseline mood levels and happiness.

-

Cursing is reported to reduce the intensity of acute pain to a statistically significantly greater extent compared to the use of other words (Stephens et al., 2009).

-

Mindfulness can help us to non-judgmentally observe the thoughts, feelings and sensations associated with the experience of pain (Mackey et al., 2022).

-

Using healthy distractions can be an effective approach to acute pain management. If we think about it, we experience more pain at night when there are fewer distractions and stimulus stimuli.

Some distraction techniques:

Enjoyable activities (walking, spending time in nature, relaxation techniques, socialising with friends, watching a film/series)

Shifting attention from yourself to someone else (e.g. do something good for another person; call a friend, etc.)

-

As the perception of pain only occurs in the brain when the stimulus is interpreted, based on our previous experience and knowledge, the key is to identify and change the negative cognitions and emotions associated with pain. Techniques within CBT are effective.

-

Stress affects the intensity, frequency and threshold of pain. If stress is experienced over a long period of time, it can lead to chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The key is to use relaxation techniques that influence the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, during which the body regenerates. Some techniques:

Breathing techniques

Listening to relaxing music

Meditation

NDSR( Non-sleep Deep Rest) protocol

-

Pain is caused by inflammation in the body, so food that increases inflammation reduces the energy available to the brain, causing fatigue and increasing the intensity of pain. Some general guidelines:

Eating an anti-inflammatory diet rich in omega-3s, vegetables, fruit, complex carbohydrates, polyphenols...

Stabilising blood sugar

Consumption of magnesium and zinc

Vitamins B1,B6,B12, C, D and E

Foods rich in capsaicin (a pungent substance found in chillies; 2.5 mg of capsaicin per serving has been shown to improve energy balance in the body; Theoharides et al., 2015)

-

There are studies confirming the effectiveness of acupuncture, but we do not yet know all the mechanisms of action (Kelly and Willis, 2019; Patil et al., 2016).

-

Poor sleep quality and quality of sleep leads to a lower pain threshold (Finan et al., 2013).

Complex regional pain syndrome

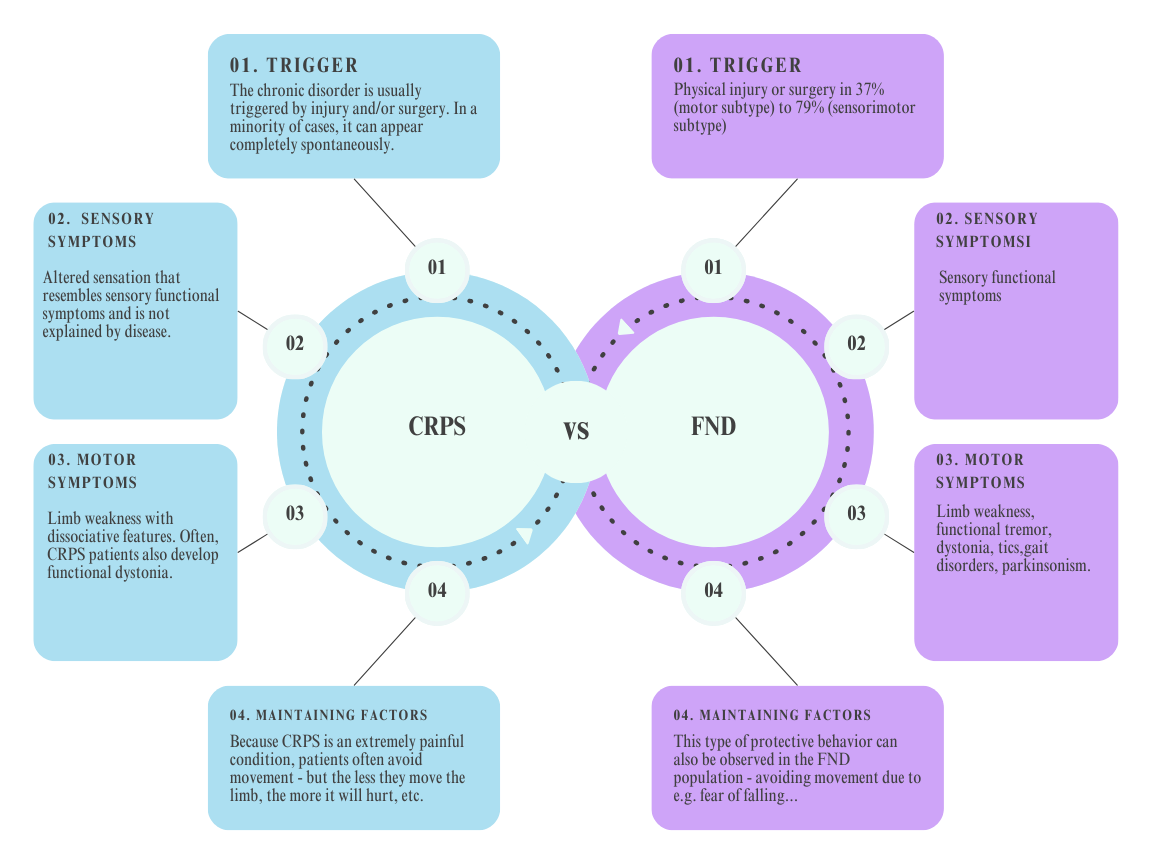

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic pain condition triggered either by physical injury or surgery, or by trauma. CRPS affects more women than men and occurs in about 20 persons per 100 000 patients, in the age range 37-53 years (Popkirov et al., 2018). CRPS is characterised by a combination of local inflammation of the body and de-regulation of the autonomic nervous system, manifested by trophic and motor dysfunction of the affected part, and closely resembles the aetiology and manifestation of symptoms of a functional neurological disorder.

Clinical diagnostic criteria for CRPS, with features also seen in functional neurological disorder

Continuous pain that is not commensurate with any stimulating event,

The patient must report at least one symptom in three separate categories:

Sensory symptoms: hyperesthesia and/or allodynia

Vasomotor symptoms: temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin colour asymmetry

Sudomotor symptoms/edema: oedema and/or changes in sweating and/or asymmetric sweating

Motor/trophic symptoms: reduced range of movement and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nails, skin)

At the time of assessment, the patient must have at least one sign in two or more of the following categories:

Sensory symptoms: signs of hyperalgesia (to needle prick) and/or allodynia (to light touch and/or deep somatic pressure and/or joint movement)

Vasomotor symptoms: evidence of temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin asymmetry

Sudomotor symptoms /edem: signs of oedema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

Motor/trophic symptoms: signs of reduced range of movement and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nails, skin)

No other diagnosis explains the symptoms better

THE GLOSSARY:

Allodynia = painful response to a painless stimulus

Hyperalgesia = increased sensitivity to painful stimuli

Edema = swelling

Sudomotor activity = change in colour and/or blood flow

-

Arntz, A., Dreessen, L., in De Jong, P. (1994). The influence of anxiety on pain: attentional and attributional mediators. Pain, 56(3), 307-314.

de Heer, E. W., Gerrits, M. M., Beekman, A. T., Dekker, J., Van Marwijk, H. W., De Waal, M. W., ... in Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M. (2014). The association of depression and anxiety with pain: a study from NESDA. PloS one, 9(10), e106907.

Finan, P. H., Goodin, B. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a way forward. The journal of pain, 14(12), 1539-1552.

Hannibal, K. E., and Bishop, M. D. (2014). Chronic stress, cortisol dysfunction, and pain: a psychoneuroendocrine rationale for stress management in pain rehabilitation. Physical therapy, 94(12), 1816-1825.

Kelly, R. B., in Willis, J. (2019). Acupuncture for pain. American family physician, 100(2), 89-96.

Kundermann, B., Krieg, J. C., Schreiber, W., in Lautenbacher, S. (2004). The effects of sleep deprivation on pain. Pain Research and Management, 9, 25-32.

Laukkanen, T., Laukkanen, J. A., in Kunutsor, S. K. (2018). Sauna Bathing and Risk of Psychotic Disorders: A Prospective Cohort Study. Medical Principles and Practice. doi:10.1159/000493392

Laukkanen, Jari; Laukkanen in Tanjaniina (2017). Sauna Bathing And Systemic Inflammation. European Journal Of Epidemiology 33, 3.

Leak RK, (2014). Heat shock proteins in neurodegenerative disorders and aging. J Cell Commun Signal 8, 4.

Mackey, S., Gilam, G., Darnall, B., Goldin, P., Kong, J. T., Law, C., ... and Gross, J. (2022). Mindfulness-based stress reduction, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acupuncture in chronic low back pain: protocol for two linked randomized controlled trials. JMIR Research Protocols, 11(9), e37823.

McCarberg, B., and Peppin, J. (2019). Pain pathways and nervous system plasticity: learning and memory in pain. Pain Medicine, 20(12), 2421-2437.

McCracken, L. M., and Turk, D. C. (2002). Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatment for chronic pain: outcome, predictors of outcome, and treatment process. Spine, 27(22), 2564-2573.

Navratilova, E., in Porreca, F. (2014). Reward and motivation in pain and pain relief. Nature neuroscience, 17(10), 1304-1312.

Navratilova, E., in Porreca, F. (2014). Reward and motivation in pain and pain relief. Nature neuroscience, 17(10), 1304-1312.

PAIN, C. (2002). Pain management: classifying, understanding, and treating pain. Hospital physician, 23, 1-8.

Patil, S., Sen, S., Bral, M., Reddy, S., Bradley, K. K., Cornett, E. M., ... and Kaye, A. D. (2016). The role of acupuncture in pain management. Current pain and headache reports, 20, 1-8.

Porreca, F., in Navratilova, E. (2017). Reward, motivation, and emotion of pain and its relief. Pain, 158, S43-S49.

Stephens, R., Atkins, J., and Kingston, A. (2009). Swearing as a response to pain. NeuroReport, 1. doi:10.1097/wnr.0b013e32832e6

Vachon-Presseau, E. (2018). Effects of stress on the corticolimbic system: implications for chronic pain. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 87, 216-223.

Villemure, C., in Bushnell, M. C. (2002). Cognitive modulation of pain: how do attention and emotion influence pain processing? Pain, 95(3), 195-199.

Wiech, K., in Tracey, I. (2009). The influence of negative emotions on pain: behavioural effects and neural mechanisms. Neuroimage, 47(3), 987-994.

Younger, J., Aron, A., Parke, S., Chatterjee, N., and Mackey, S. (2010). Viewing Pictures of a Romantic Partner Reduces Experimental Pain: Involvement of Neural Reward Systems. PLoS ONE, 5(10), e13309. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013309